The Colombian Army keeps quiet on reports of attacks in the Guayabero region

Internal documents from Colombia’s General Command of the Military Forces leaked by the Guacamaya ‘hacktivist’ collective reveal the military received accusations of abuses during forced eradication operations in 2020, including reports of a journalist and several farmers who were shot. According to the documents, more reports of abuses were logged in 2021.

The Guardia Campesina, an unarmed community-based security force, and residents of the Guayabero region protest coca eradication operations in November 2021 in Puerto Cachicamo, in the municipality of San José del Guaviare. Credit: Edilson Álvarez/Voces del Guayabero.

By Rutas del Conflicto, La Liga Contra el Silencio y CLIP

Translation: Sandra Cuffe

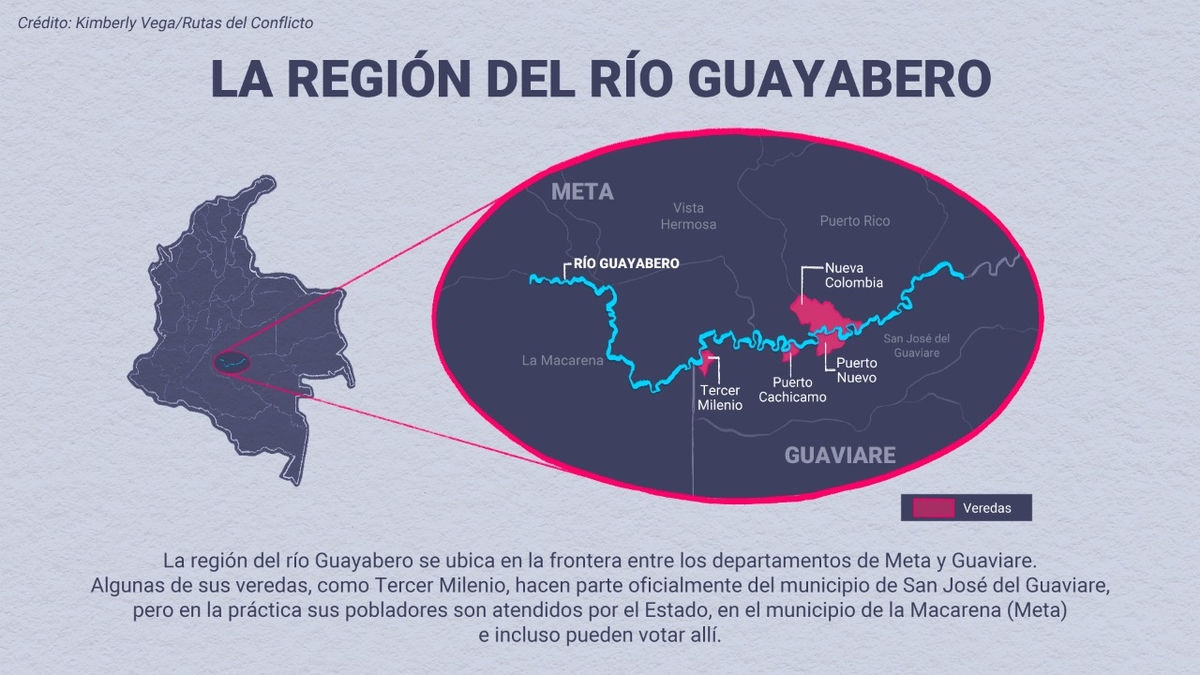

Military forces have received and internally processed more than ten reports of alleged human rights violations committed by soldiers since June 2020 in the Guayabero River region, in southeastern Colombia. However, they have kept quiet about the results of their investigations, according to information accessed by Rutas del Conflicto via Forbidden Stories, a consortium of journalists based in France that pursues and publishes the work of journalists who have been threatened or killed.

Military abuses were reported in at least five of the more than 90 villages that comprise the Guayabero region, between the Meta and Guaviare departments. They came to light two and a half years ago when at least six people were injured by gunshots during operations for the forced eradication of coca. One of the wounded was Fernando Osorio, a journalist from the Voces del Guayabero community media outlet, who was shot in the hand, and a second bullet hit his camera bag. Other reporters from the media outlet told Rutas del Conflicto in interviews they had been called “the guerrillas’ photographer and journalists,” a stigmatizing association they said has put them at risk, given the military’s decades-long armed conflict with guerrilla forces. Aside from the reporter who was shot, journalists from the community outlet also recounted that at different times soldiers had detained them, prevented them from reporting, and forced them to delete photographs and video footage from their cameras.

The attacks had an impact on Voces del Guayabero, a community media outlet that publishes content on Facebook. In 2020, their videos about the eradication operations were republished and broadcast online and on television by national-level media. The consequences of the coverage, though, ended up affecting the community media outlet, with a reduction in the team. Reporters experienced fear from the attacks, Osorio stepped back from journalism after his hand was affected by the gunshot, and others had less time due to family and work obligations. The team had started out with five reporters but by mid-2021 it was down to a single journalist.

Voces del Guayabero has since bounced back and seven community journalists are involved, following a process of dialogue and training in partnership with El Cuarto Mosquetero, an online independent media outlet based in Villavicencio, capital of the Meta department. The increased visibility also contributed to an end to attacks by military forces, according to the journalists. However, they still have not received any response about investigations of abuses, two and a half years after the first reports.

The Army knew about the accusations of military abuses in 2020, as well as new reports the following year. That is revealed in documents from the General Command of the Military Forces leaked by the Guacamaya ‘hacktivist’ collective.

Rutas del Conflicto had access to the records via Forbidden Stories. In most cases, public reports condemning human rights violations and statements recounting attacks against farmers were circulated by non-governmental organizations and made their way to the Army through state institutions, including the Office of the Inspector General (Procuraduría General de la Nación), Office of the Ombudsman (Defensoría del Pueblo), and Ministry of Defense. Civil society organizations use public denunciations as a mechanism to make human rights violations known and request clarification from authorities.

A mural highlights Campesino Resistance in the village of Nueva Colombia, in Vista Hermosa, Meta. Credit: Rutas del Conflicto.

A June 25, 2020 document from major general Sergio Alberto Tarfur García, then commander of the southeastern Joint Command #3, informed brigadier general Raúl Hernández Flórez, at the time the commander of the Omega Joint Task Force that operates in the Guayabero region, about a statement the National Association of Campesino Reserve Zones (ANZORC) sent to the regional Ombudsman’s Office location in Meta. The statement reports “indiscriminate” gunshots between June 5 and 15, 2020 wounded six people, including a reporter. The Ombudsman’s Office forwarded the information to the regional Inspector General’s Office representative in Meta, who then sent it to the General Command of the Military Forces (see the document).

That same day, Tarfur García also briefed the Omega Joint Task Force commander at the time about two other public statements civil society organizations had sent to the regional office of the Ombudsman’s Office in May 2020 that were sent on to the military command. The first statement reported three farmers were injured by military forces in the Guayabero region. The second claimed military forces had not been complying with Covid-19 public health protection protocols. The document also asserted some military personnel were not wearing any identification and covered their faces, some verbally and physically assaulted farmers, and some referred to local farmers as “guerrilla and militia members” (see the document).

In an interview with Colombian media, brigadier general Hernández Flórez also referenced a supposed relationship between the farmers who were opposing forced eradication and illegal armed groups. The Omega force commander at the time claimed his troops were “constrained and obstructed by means of violent protest”. He also said residents were taking action “under the pressure exerted by ‘Gentil Duarte,’ ‘Maneto’ and ‘Leopoldo,’ aliases of members of the Seventh Structure of the Residual Armed Group”, according to a June 4, 2020 report published by RCN Radio. ‘Residual’ groups are armed fronts originating from members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) who opposed the 2016 peace accords and never demobilized.

The presence of the illegal armed organization in the Guayabero region is apparent, as Rutas del Conflicto observed on the ground, where banners do not refer to the Seventh Structure but instead to the Jorge Briceño Suárez Front, formed after the FARC laid down its weapons. “I am alive and on a warpath against the global imperialism of the north, against the national oligarchy on its knees and its repressive apparatus,” reads one of the banners attributed to alias ‘Gentil Duarte,’ who was declared presumed dead by the government in May 2022.

There are at least two styles of banners in villages such as Puerto Nuevo and Nueva Colombia, one of them in tribute to FARC women and the other attributed to the FARC. At least four military documents in the Guacamaya leak address the presence of illegal armed groups in the area. A May 26, 2021 intelligence analysis document claims the Jorge Briceño front traffics drugs along the Guaviare and Guainía Rivers toward the Venezuelan border.

Local farmers and other residents maintain that when military forces associate them with the illegal armed group it puts them at risk but that it also makes them a target for other armed groups such as the ‘Águilas Negras,’ which residents say have circulated pamphlets with threats. They also explain they have protested against forced eradication because they have no alternative to substitute their coca crops with some other way of making a living.

“If they want to put an end to coca in the region, where would we get food like we do by cultivating coca leaves? We have always been up for dialogue. […] They have shown up arbitrarily and violently. It is a shame that it is the military, not an illegal group, that is lashing out at us,” a resident who asked not to be identified for security reasons told Rutas del Conflicto when the publication visited in December 2022.

Journalists from Voces del Guayabero and El Cuarto Mosquetero trace the outline of a mural from a projection in Nueva Colombia, Meta. Credit: Rutas del Conflicto.

Journalists from Voces del Guayabero and El Cuarto Mosquetero trace the outline of a mural from a projection in Nueva Colombia, Meta. Credit: Rutas del Conflicto.

The local farmer also said that residents grow yucca and plantains in the region but there is no infrastructure that allows people to sell those crops outside the village. “We need to make a living from something. We always ask the State and the government not to treat us like drug traffickers,” he said. Residents oppose aggression during military operations as well as the Army’s seizure of cattle that grazes inside the Serranía de La Macarena Natural National Park.

The mission of the Omega Joint Task Force is to combat illegal armed groups and transnational crime in Meta, Caquetá and Guaviare, and it has led forced eradication in the region. Tarfur García and Hernández Flórez are no longer Omega commanders, according to a December 2021 public statement by the Army.

New threats and stigmatization

Public statements condemning reported attacks by Army personnel continued in 2021. The military received at least ten new complaints composed by various groups: Norman Pérez Bello Claretian Corporation; Office of the Ombudsman; Peaceful Mobilization for the Defense of Human Rights, Life, Peace and Territory; and the Guayabero Campesino Humanitarian Space. The Humanitarian Space was established in 2020 by various human rights, faith-based and civil society groups to raise public awareness about aggression and attacks against local communities. In March 2022, the Inspector General of the Military Forces sent a formal letter to the Omega force to request a response to the complaints (see the document).

A document circulated by the Humanitarian Space in March 2021 reports military forces threatened residents and restricted their movements in Caño Cabra Alto, Meta (see the document). Another complaint dated July 26, 2021 notes intimidation in Nueva Colombia, where 20 soldiers entered the home of a local woman. That incident took place when community leaders were in the Valle del Cauca department for dialogue with the government of then president Iván Duque (see the document). Another statement highlights “stigmatization [and] threats by member of the Army” in November 2021 against campesinos in the village of Puerto Cachicamo, Guaviare (see the document).

Rutas del Conflicto sent the General Command of the Military Forces questions in early January 2023 concerning the status of investigations into the complaints, but as of the publication of this article the military has not responded. The Ministry of Defense responded, indicating the General Command would address questions specifically related to the Guayabero region. Humanitarian Space member organizations never received responses either.

“Most of the complaints lodged with previous administrations never received a response. […] We hope that the institution starts to respond under this new administration,” said a member of the National Association of Campesino Reserve Zones (ANZORC) who requested not to be identified for security reasons. The Colombian government changed hands in August 2022, when president Gustavo Petro took office.

Daniel Ávila, technical secretary of the Plains & Forest Network (Red Llanos & Selva) and a member of the Norman Pérez Bello Claretian Corporation, told this reporting partnership that forced eradication operations continue in the Guayabero region, as does the presence of the military and other armed groups. The failure of state institutions to respond to complaints is a repetitive trend, according to Ávila. He considers the contributing factors to that trend are state abandonment and marginalization of the Orinoco and Amazon regions, a “peculiar interest in land use” in the area, related to territorial control, and public policy on natural parks excluding rural residents.

Edilberto Daza, legal representative of the Foundation for the Defense of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Eastern and Central Colombia (DHOC), told this reporting partnership that the response he received was legal action filed by Raúl Hernández Flórez, who accused non-governmental groups that made public statements of allegedly violating his rights to reputation and honor. The judicial system dismissed the accusation.

The leaked military documents also contain instances of stigmatization of social movements and civil society organizations. One of the texts, sent on April 22, 2021 by members of the General Command, claims that armed groups would have influence over three specific organizations as well as human rights organizations in general. Two months later, slides with an analysis about the paro nacional nationwide protest movement mention the Jorge Briceño front could possibly have influence on the social movement. However, the document provides no evidence of the alleged association. The General Command of the Military Forces was asked about stigmatization but did not respond.

When Colombian senators sent questions about the same events in the Guayabero region, the military did respond. A response in May 2021 signed by general Jorge León González Parra, head of the joint chiefs of staff at the time, indicates preliminary inquiries are underway in accordance with a 2017 military disciplinary regime law, “with the aim of obtaining more information with regard to the complaints and taking disciplinary action in line with the law.” According to the document, there are constant trainings on human rights. With regard to the statements by the Humanitarian Space, the May 2021 correspondence explains that five of the complaints had been sent to the armed forces and that the military had accessed three others online. Between June 2020 and January 2022, the various organizations that comprise the Humanitarian Space circulated 16 public statements condemning human rights violations in the Guayabero region.

Stigma against community journalism

Two reporters from Voces del Guayabero began covering the forced coca eradication operations in Tercer Milenio, Meta, when they started in May 2020. Another two journalists stayed in Puerto Nuevo, Guaviare, to receive and publish coverage on Facebook. There was no internet access on the ground where operations were taking place, so the journalists traveled by boat along the Guayabero River between the two communities to download video footage, according to Maritza Montoya Moreno, 34, who was one of the community reporters at the time and is now community council president in Caño San José, Meta.

Voces del Guayabero was the only media outlet on site at the outset of the eradication operations. Its videos were included in national media broadcasts reporting on gunshots fired at farmers and the injured and the reports included military sources who accused residents of violence against soldiers and of associations with illegal armed groups.

The community media outlet was established in 2018 to report on events in the region, including military operations, from the perspective of its local residents, and to denounce human rights violations. “We put out things narrated by the people directly affected,” affirms Salomón Bedoya Pulido, 42, a Voces del Guayabero reporter in Lejanías, Meta. The outlet initially published in WhatsApp groups for more local audience, but have used Facebook since 2020.

The first five community reporters experienced aggression and persecution from military forces during eradication operations. “We need to hit the one with the camera,” they overheard. Stigmatization against the Voces del Guayabero is multifaceted. It is also connected to discourse and narratives about farmers and other rural residents of regions affected by the armed conflict, and to discourse and narratives about community reporters who do not have university degrees. In Colombia, a degree is not a prerequisite for practicing journalism. The country’s Constitutional Court abolished the need for professional accreditation in 1998, in its C-087 sentence. “Regional journalism poses more risk. [The reporters] are very exposed,” says Lina Álvarez, founder of El Cuarto Mosquetero, a publication that has covered and led journalism workshops in the Guayabero region.

Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP) director Jonathan Bock notes community and alternative reporters are often not recognized as journalists by actors such as the military. “The lack of response when the people attacked are community journalists is quite symptomatic. In addition to that, when an institution is involved, in this case the Army, it is much harder for investigations to make progress,” he says.

Bock also pointed out that the communications system the Army has developed includes 150 radio stations, which has created a monopoly on local radio in much of the country. Military forces have also frequently associated alternative voices with illegal groups without providing any evidence of an association, according to Bock. FLIP has requested state protection for Voces del Guayabero journalists and has filed requests with the Office of the Inspector General and the Army for information concerning the attacks. In August 2020, the Army responded, telling FLIP it was conducting a disciplinary investigation related to the incidents in question, and that it was the stage of proceeding with interviews and verification of reports. No further progress has been made known. The Office of the Inspector General informed Rutas del Conflicto this past January that it was processing six complaints about the alleged abuses in the Guayabero region and that it had sent the information to the military, police, governors, and local municipal governments.

Another factor behind the stigmatization of Voces del Guayabero is that fact that in recent years some new reporters identify as former FARC members who demobilized and signed the peace accords. Ex-combatants have reintegrated into civilian life but face threats and 355 of them have been killed around the country since the peace accords were signed in November 2016, according to the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia. Disquiet is present in the Guayabero region too.

The military’s direct threats against Voces del Guayabero journalists ceased with national and international awareness of the situation in 2020. The reporters believe journalism workshop sessions with El Cuarto Mosquetero have brought increased respect to their community outlet.

Journalism training and ongoing challenges

The relationship between El Cuarto Mosquetero and Voces del Guayabero started with the coverage of the military operations in 2020. The joint ‘itinerant school’ training sessions formally kicked off in November 2021 with workshops that included writing, dramatization, radio, photography and video that also delved into issues such as gender, peace and territorial defense. They also painted murals in Nueva Colombia. The journalistic projects completed during the training sessions included reports on local health care and the unarmed, community-based guardia campesina protection force, among other issues. The alliance with El Cuarto Mosquetero also opened new doors for Voces del Guayabero, which contributed in 2022 to coverage by El Espectador, a national newspaper.

Ronald Echeverry, 55, has been one of the participants in the workshops. He was one of the founders of Voces del Guayabero back in 2018, when he was president of the community council in Nueva Colombia. “I am going to participate too. It isn’t fair to just be at a distance,” says Echeverry, who took part in the journalism school sessions alongside two of his children, aged 11 and 9. As a child, Echeverry wanted to be a radio sportscaster. Today he uses his cell phone to report on his village and rural life.

Dora Martínez Apache, 33, is another reporter who joined the Voces del Guayabero team as a result of the workshops. Among the new goals she sees for the media outlet are coverage of the sorry state of rural infrastructure, the lack of a good hospital, and a dearth of educational opportunities for children and teenagers after the fifth grade. “It is when we work that other people can find out how we live,” she says.

Salomón Bedoya, Martínez Apache’s partner, had previously seen Voces del Guayabero’s work. He was in WhatsApp group chats with other community leaders and they circulated the community outlet’s videos back when it was just getting started. Another reporter, who requested her name not be published for security reasons, is a demobilized ex-combatant who signed the peace accords. She had been a nurse while she was part of the FARC, and in 2020 she treated Osorio, the reporter who was shot in the hand. A year and a half later, she decided to participate in the journalism workshops.

The new Voces del Guayabero journalists have joined founders like Edilson Álvarez in the ongoing task of recounting what happens in the region. However, the challenges are substantial. Beyond the failure of officials to clarify investigations into human rights violations, the stigmatization and the presence of illegal armed groups, the community reporters also have work, family and community leadership responsibilities.

Forced eradication continues to this day, according to several sources. In November 2022, residents encircled soldiers in Lejanías using a peaceful protest tactic called a cerco humanitario, which resulted in the presence of government officials and a promise of dialogue. In January 2023, though, there was a new mobilization in Lomalinda to demand progress in negotiations over the criminalization of rural residents related to deforestation in protected areas, cattle ranching in the region, and illicit crops. In the meantime, the Voces del Guayabero reporters and other residents are still waiting for a response to the complaints of human rights violations over the past three years.

Actualizado el: Mar, 02/07/2023 - 15:52