Enforced disappearance is one of the darkest nuances of war. Not only it affects every right of the victims, but the perpetrators seek to erase the existence, the bodies, and the memories of those lives. In Colombia, in accordance with numbers from the National Center for Historical Memory, at least 942 municipalities out of the 1,122 that exist in the country have suffered from this crime that not only causes enormous pain and confusion to the families of the victims, but also affects entire communities in different ways.

Thousands of people are still looking for their missing ones, and the suffering and permanent uncertainty to which they are exposed generates an anguish that remains over time, causing them chronic stress, depression and anxiety. This "grief" and lack of closure leaves deep wounds both physical and emotional that if not treated properly, can aggravate the health of those who try to find their relatives.

Living with that unhealed wound, and with the constant stress that it produces, is manifested in the body. “It has been seen that psychological stress and the immune system have reciprocal defenses, that is to say that one takes actions on the other; in that order, states of anxiety and depression can cause chronic inflammatory states that predispose to many other pathologies”, explains Patricia Álvarez, an expert gastroenterologist. “I have been ill since the day my son disappeared. I got womb cancer. Doctors told me it was because of the anguish, because I didn't eat, I got very sick, I got severe depression and I still have it. A doctor gave me a medical incapacity. It says that I have multiple illnesses. The doctors tell me that the pain came out through my skin”, says Edilia Payán, mother of Jonathan Uzcátegui Payán, who disappeared in 2004 in hands of the paramilitaries of the Calima Block, in Cauca.

Despite the State's efforts to give psychological care for the victims, these have been insufficient both in terms of coverage and in quality of the treatments offered. The main mechanism for providing health services is the Ministry of Health’s Program for Psychosocial Care and Comprehensive Health for Victims (Papsivi). Its main function is to "offer differential care, a comprehensive rehabilitation strategy for the recovery or mitigation of the damage caused by the conflict and contribute with unity and collaborative work in the communities", explains Hernando Millán, a staff member of the social promotion office of the Ministry of Health that is in charge of the management of Papsivi.

Another entity in charge of this type of psychosocial care is the Victims Unit, which has the obligation to support Papsivi's work plan, complement it with the Emotional Recovery Strategy proposed by the Ministry, and follow the route of accompaniment to the relatives of the missing ones during the process of the decent delivery of the body.

In practice, Papsivi has very limited coverage: since it was created in 2011 with the Victims Law, it has barely attended 5,857 people out of the 129,109 relatives of missing people registered in the Unique Registry of Victims (RUV), that is, barely 4.5%. It is important to say that those victims who are not in the RUV cannot access these psychosocial care services.

In addition, Papsivi only has the capacity to reach the municipal capitals. According to the Ariari Victims Association, a group from the central-eastern part of the country on the bank of the Ariari River in the department of Meta, the program, which was carried out in the area between 2016 and 2017, was not implemented in the rural areas of the department, where several communities affected by the violence on late 1990s and early 2000s are concentrated. That is one of the great shortcomings of the program.

Definitely, the numbers show a lack of coverage. For this investigation, the journalistic team of Rutas del Conflicto built a database with statistics and testimonies from relatives and groups of victims of the armed conflict in 24 municipalities with a high number of missing people in the country, according to data from the Memory and Conflict Observatory of the National Center for Historical Memory and the Victims Unit. The chosen municipalities belong to 15 departments located in all the geographical regions of the country.

It was found that, for example, the municipality of Turbo in Antioquia has at least 1,355 missing persons and there are 2,451 relatives registered in the RUV looking for them. However, according to the Ministry of Health, only 58 people have been treated by Papsivi with a forced disappearance approach: that is 2.3%. Of the 24 municipalities that Rutas del Conflicto reviewed, Florencia in Caquetá is the one that reports the highest number of attention focused in this victimizing act with 107 victims attended, which represents 8% of those who are recognized in the RUV.

In large cities, the figures of attention given to victims of this crime don’t get better. Medellín has 3,913 people registered for this occurrence and only 148 have been treated, about 4%. In Bogotá, where there are 1,090 people on the RUV, the Papsivi has reached to 118 people, a 10.8%. Cali has 845 people registered for forced disappearance and 155 have been cared for, reaching 18%.

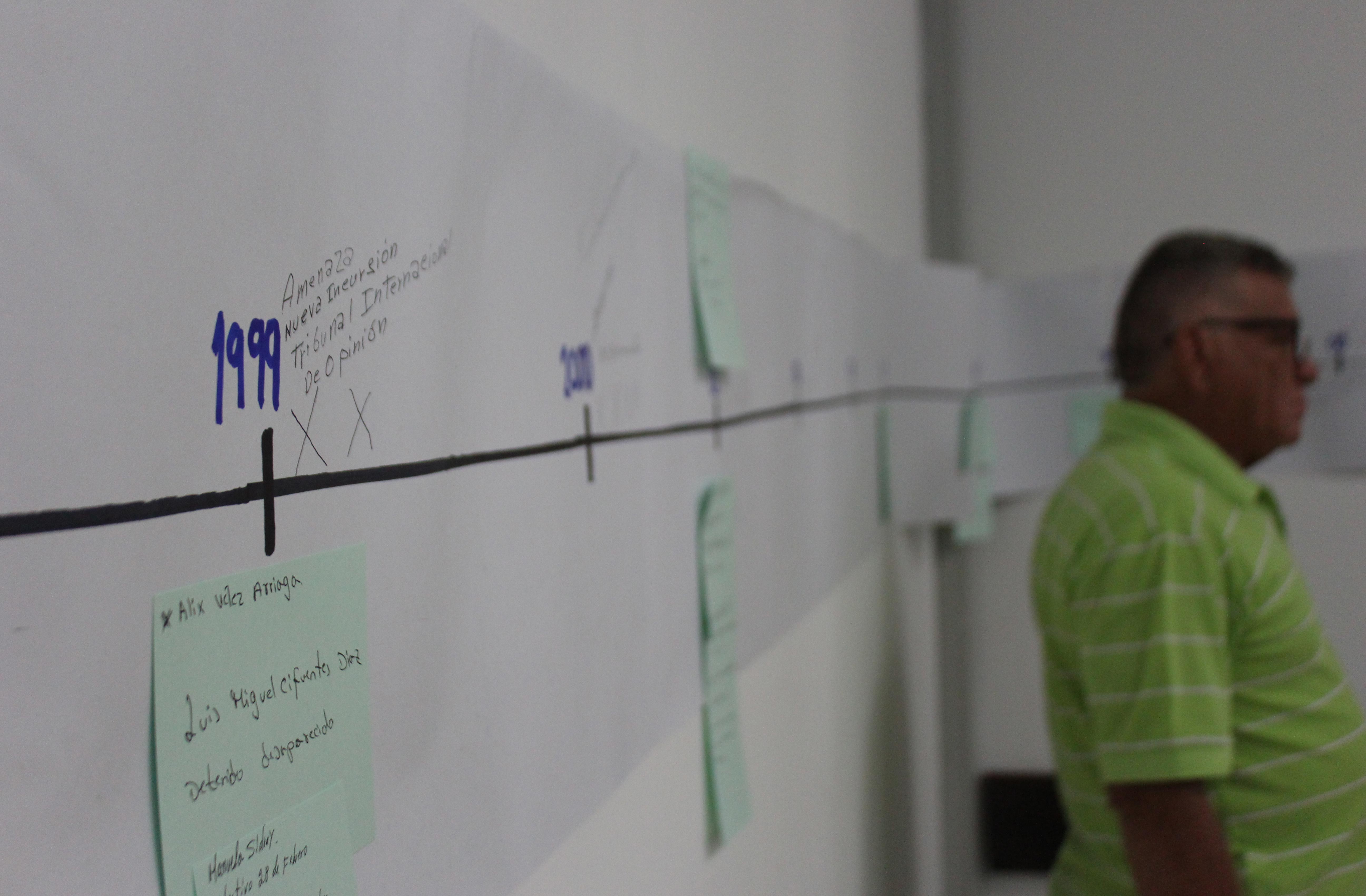

In addition to coverage, the other major flaw of psychosocial care is the quality of therapies. In the Papsivi’s case, the implementation of the program has not been successful every time and the victims end up dropping out of it without completing their cycle of care. In other cases, the problem appears when the responsibility for the treatment is in the hands of the EPS. “I took my son to the psychologist because one day he told me, 'Mommy, what should I live for?' That scared me. The psychologist asked my son how he saw himself within five years and he replied that he didn’t know. So the doctor told me: "Ms., sign up your son to study something about gluing pipes because your son isn’t good enough to be an engineer." That destroyed me and he said it without knowing my son's pain. Today my son is studying systems engineering”, says Alix Vélez, wife of Miguel Cifuentes, who disappeared in the massacre committed by the Self-Defense Forces of Santander and Sur del Cesar, AUSAC, on February 28th, 1999, in Barrancabermeja.

For therapists, the management of pain with relatives of missing people is challenging because they cannot fully treat it from the point of view of grief and its stages, since there is no certainty about the death of the person and no acceptance of the loss. “A duel is made over something that is no longer there; the life of that person who left leaves a void and mourning is the process of resolving that void”, explains Miguel Gutiérrez, PhD in Psychology, professor and researcher at the Universidad del Rosario, who adds that a correct way for experts is for them to accompany the person in the search for their own solutions.

However, many times neither the resources nor the workforce, that is, the psychosocial teams, are enough to provide quality care. According to Aída Solano, coordinator of the psychological care of the Victims Unit, the number of people they need to attend is overflowing the professionals and they have to outsource the service. And, although the Unit trains such contractors, "sometimes they deceive us," says Solano. "We call the recipients of the service and they tell us that the psychologist did not return, but the professional reports desertion or lack of interest from the victims," says the official.

The problem, according to the victims, is that many times the professionals don’t know how to treat them and end up affecting them even more. "There are specific demands from populations that need well-trained professionals to intervene on an emotional and psychological level, but unfortunately there are none", says Gutiérrez. Precisely, in Colombia, a country in conflict, there are few training options offered by the academy to psychologically attend these people and, additionally, there are few professionals specialized in this approach.

Although the pain of the communities sometimes ends up re-victimizing family members who are looking for their loved ones, victims organizations and many of those who have witnessed the horror of this crime have created ways of not forgetting and give a new meaning to the lives of those who are still absent. Groups have been consolidated throughout the country to remember the missing people and to demand truth, justice and reparation from the State. The union and work of these groups of victims and the rituals that they have collectively constructed have served as an emotional support to mediate their pain and to keep the memory alive amid the social indifference that surrounds them. “As a social action they have a very important value. It goes against the act of completely erasing a person. They manage to restore some of the dignity that was taken from them, ”explains Miguel Gutiérrez.

The claim to the State is a common element in these organizations and has given them a leadership role that they did not have before. Alejandro Álvarez, a psychologist and researcher who has collected the support practices of the largest organization of the disappeared in Colombia, the Association of Detained and Disappeared Relatives (Asfaddes), explains that the development of a political component that empowers victims to claim their rights is key in their psychological care. “Asfaddes, in its growth as an organization, has learned that it is important for victims to be aware of the value of their collective work so that there is no impunity. This work turns them into active subjects, who identify themselves as valuable people who vindicate their rights”, explains Álvarez.

Despite the efforts of the communities, it’s essential that the State improves their care. Experts point out that it is also important for universities to join in to improve the training of psychologists and to bring training programs to the regions most affected by these crimes.

To get to know in detail the research on mental health in the relatives of those missing by the violence in Colombia, explore the series of reports: Unhealed scars: stories, bodies and minds marked by the disappearance in Colombia, in Rutas del Conflicto.

Direction:Óscar Parra Castellanos

Edition:Óscar Parra Castellanos and Ginna Santisteban Calderón

Research:Santiago Luque Pérez, Óscar Parra Castellanos,

Pilar Puentes and Ginna Santisteban Calderón

Data visualization:Paula Hernández and Santiago Luque Pérez

Audiovisual production:Jessica Santisteban Calderón

Photographs and videos:Álvaro Avendaño, Samara Díaz and Santiago Luque

Illustrations:Kimberly Vega

Design and assembly:Paula Hernández

Translation:Paola Llinás

Published on 20 August 2020

Direction:

Óscar Parra Castellanos

Edition:

Óscar Parra Castellanos

Ginna Santisteban Calderón

Research:

Santiago Luque Pérez

Óscar Parra Castellanos,

Pilar Puentes

Ginna Santisteban Calderón

Data visualization:

Paula Hernández

Santiago Luque Pérez

Audiovisual production:

Jessica Santisteban Calderón

Photographs and videos:

Álvaro Avendaño

Samara Díaz

Santiago Luque

Illustrations:

Kimberly Vega

Design and assembly:

Paula Hernández

Translation:

Paola Llinás

Published on 20 August 2020